Se siete stati nei musei vaticani e avete gironzolato per le sale ammirando il vasto assortimento d’arte e scultura, allora sicuramente vi siete imbattuti anche nelle stanze di “Raffaello” situate al secondo piano dei Palazzi Vaticani.

If you have been to the Vatican museums and wandered through the halls taking in the vast assortment of art and sculpture, then indeed you have also happened upon the “Raphael” rooms located on the second floor of the Vatican Palace.

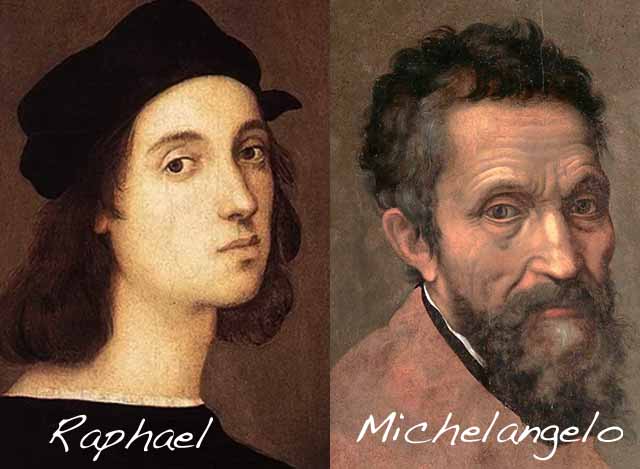

Dal 1509 al 1511, Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino, già un “rockstar” dei pittori insieme a Leonardo e Michelangelo, fu chiamato a Roma per lavorare per Papa Giulio II. Giulio fu eletto Papa nel 1503 dopo uno dei conclavi più brevi, per il fatto che corrompeva tutti. Era un Papa militarista, che comandava eserciti; fu anche un estimatore della grande arte e commissionò alcune delle più grandi opere. Per consolidare la sua eredità papale chiamò a Roma Raffaello e Michelangelo, il primo per decorare le sue stanze personali, l’altro per decorare il soffitto della Cappella Sistina.

In 1509 through 1511, Raphael Sanzio from Urbino, a rock star of painters at the time along with Leonardo and Michelangelo, was called to Rome to work for Pope Julius II. Julius was elected pope in 1503 after one of the shortest conclaves—due to the fact he bribed everyone. He was a militaristic pope who commanded armies; he was also an admirer of great art and commissioned some of the greatest works. To solidify his papal legacy he called Raphael and Michelangelo to Rome—the first to decorate his personal rooms, the other to decorate the ceiling in the Sistine chapel.

Papa Giulio sperava di eclissare i dipinti del primo Rinascimento negli appartamenti Borgia del suo predecessore Papa Alessandro VI che aveva occupato le stanze direttamente sotto le sue. È stata una mossa coraggiosa da parte sua chiedere a Raffaello di dipingere così vasta scala di affreschi nei sui appartamenti, così come per lui a chiedere a Michelangelo di disegnare il ciclo di affreschi nella Cappella Sistina. Nessuno dei due artisti avevano esperienza lavorare in affresco: Raffaello era noto per piccoli ritratti e dipinti religiosi su legno e pale d’altare, e Michelangelo per lo più era a suo agio nel lavorare la pietra.

Pope Julius hoped to outshine the early Renaissance paintings in the Borgia Apartments of his predecessor Pope Alexander VI who had occupied the rooms directly below his. To this end, he tasked Raphael with decorating his private chambers. It was a gutsy move on his part to request Raphael paint such a grand scheme of frescos, just as it had been for him to ask Michelangelo to design the fresco cycle in the Sistine chapel. Neither artist had experience working in fresco; Raphael was known for small portraits and religious paintings on wood and altarpieces, and Michelangelo mostly was comfortable working in stone.

Forse, perché entrambi gli artisti—che fra di loro non correva buon sangue—eccellevano nel produrre opere stellari proprio a causa della loro rivalità: nessuno dei due voleva fallire e si è lanciato brillantemente nella sfida.

Perhaps, because both artists didn’t like each other

very much, they excelled in producing stellar

work precisely because of their rivalry—neither

wanted to fail and rose brilliantly to the challenge.

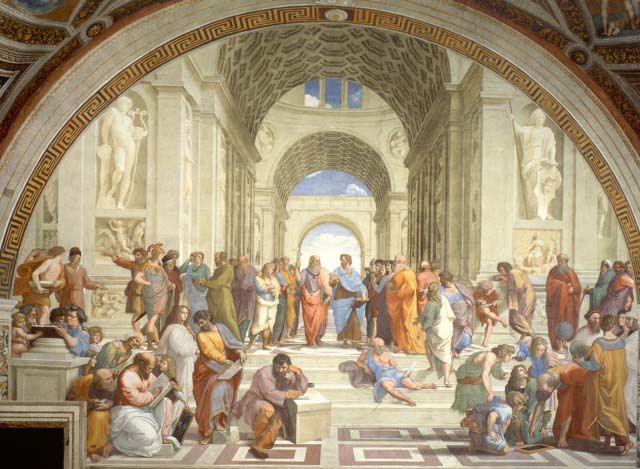

In particolare l’affresco di Raffaello “la Scuola di Atene” che si trova nella Stanza della Segnature che doveva essere la biblioteca di Giulio, è un brillante esempio del matrimonio tra arte, filosofia e scienza—la premessa per l’intero movimento rinascimentale italiano. Sembra opportune decorare lo studio del Papa con i ritratti di grandi pensatori. Chiunque fosse entrato nella sala sarebbe rimasto colpito dall’estrema cultura e ampiezza di conoscenze del nuovo Papa.

Most notably Raphael’s fresco “The School of Athens” located in the Stanza della Segnatura which was to be Julius’ library, is a glowing example of the marriage of art, philosophy, and science the premise for the entire Italian Renaissance movement. It seems apropos to decorate the Pope’s study with portraits of great thinkers. Anyone entering the room would have been impressed by the extreme culture and breadth of knowledge of the new Pope.

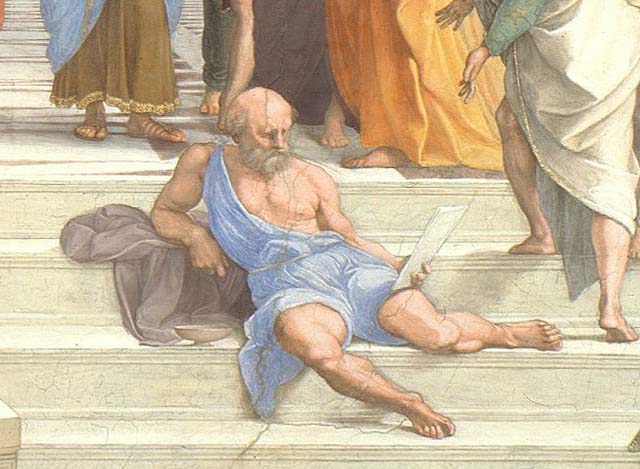

L’affresco è composta da gruppi di antichi filosofi e studiosi greci

che illustrano i vari modi di vedere il mondo attraverso diverse ideologie.

The painting is composed of groups of ancient Greek philosophers and scholars

who illustrate the various ways of viewing the world through different ideologies.

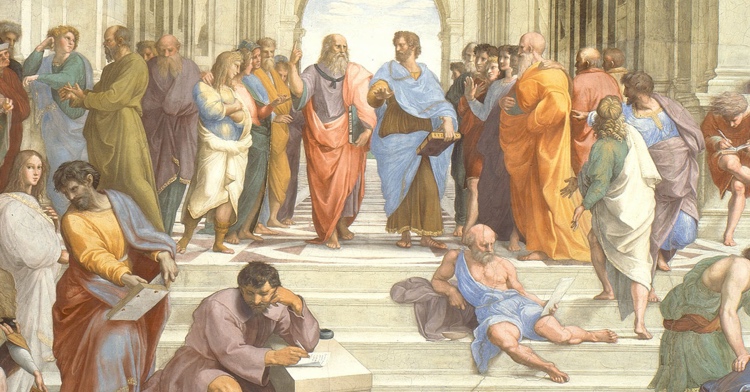

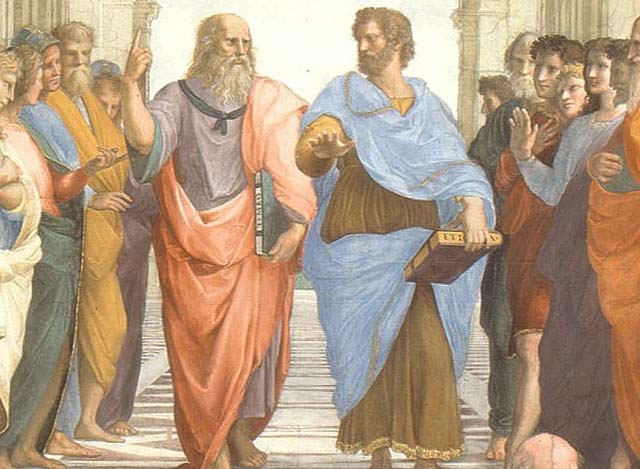

Le figure nell’affresco sono posizionate, come su un palcoscenico teatrale. Il primo gruppo di grandi pensatori che lo spettatore osserva, perché sono posizionati nel centro incorniciato dall’arco dietro loro, sono le figure di Platone ed Aristotle.

The figures in the fresco are positioned as if on a theatrical stage. The first set of great thinkers the viewer beholds, as they are positioned in the center of the scene framed by the arc behind them, are the figures of Plato and Aristotle.

the general Alcibiades and Aeschines of Sphettus.

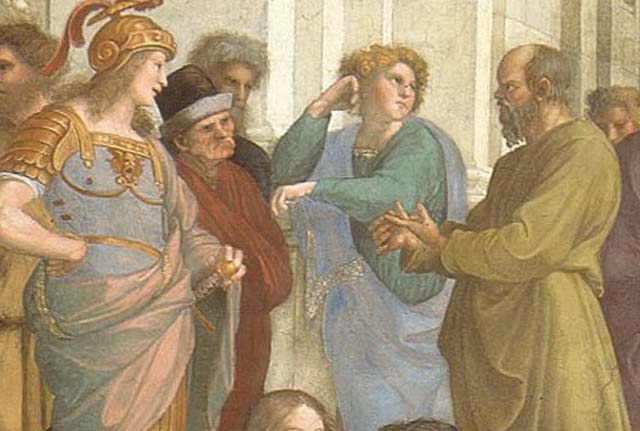

Mentre l’occhio dello spettatore si muove intorno alla complessa panoplia, inizierà a indovinare altri pensatori notevoli. Alla sinistra di Platone si trova Socrate, riconoscibile da un antico busto ritratto del filosofo che si dice Raffaello abbia usato come suo modello. Socrate é raffigurato mentre parla con i suoi studenti, il generale Alcibiade e Eschine di Sfetto.

As the viewer’s eye moves around the complex panoply, he will begin to discern other notable thinkers. To the left of Plato is Socrates, recognizable from an ancient portrait bust of the philosopher that Raphael is said to have used as his guide. Socrates is pictured talking with his students, the general Alcibiades and Aeschines of Sphettus.

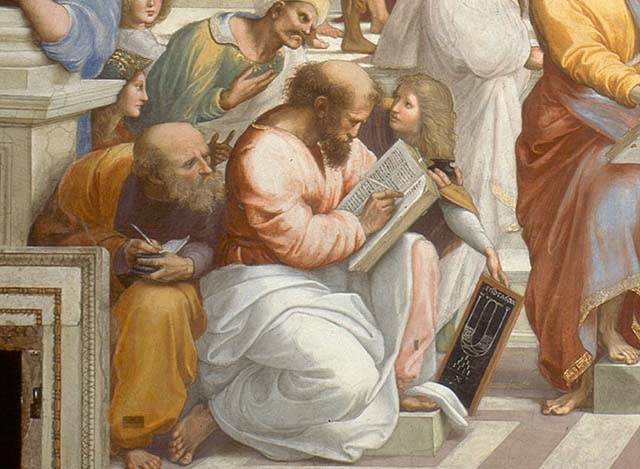

In basso a sinistra, Pitagora, noto per le sue scoperte matematiche e scientifiche, scrive in un libro, mentre uno dei suoi assistenti tiene un diagramma su una lavagna.

In the lower-left, Pythagoras—known for his mathematical and scientific discoveries—writes in a book, as one of his assistants holds a diagram on a blackboard.

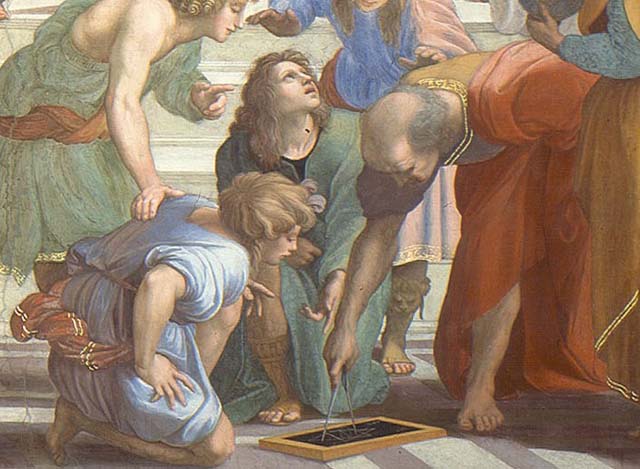

Sul lato opposto, Euclide, il padre della geometria, è raffigurato piegato su un disegno con un compasso. Accanto a lui c’è l’astronomo Tolomeo, che tiene in mano un globo terrestre. Uno dei suoi studente sbircia lo spettatore, ed è nientemeno che di Raffaello, che si dipinge nella scena!

On the opposite side, Euclid, the father of geometry, is depicted bent over and drawing with a compass. Next to him is the astronomer Ptolemy, who holds up a terrestrial globe in his hand. One of his students peeks out at the viewer, and it is none other than Raphael who paints himself into the scene!

Nel primo piano è la figura di Diogene, il fondatore della filosofia cinica. Viene mostrato separato dagli altri poiché Diogene credeva nel vivere una vita semplice evitando le convenzioni culturali.

In the foreground is the figure of Diogenes, the founder of the Cynic philosophy. He is shown apart from the others as he believed in living a simple life avoiding cultural conventions.

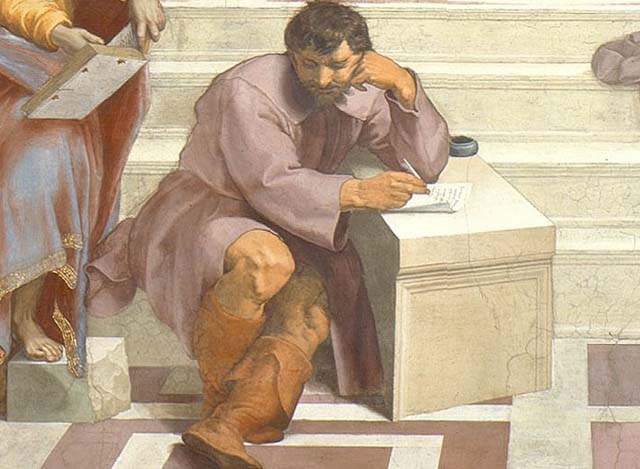

È interessante notare che un’altra figura, isolata a sinistra di Diogene, è mostrata nella classica posizione del “pensatore.” Questo rimuginante e pensieroso uomo si dice sia il filosofo Eraclito che ha lasciato la sua vita privilegiata per vivere una vita solitaria. Era considerato un misantropo a causa del suo odio generale, antipatia e sfiducia nei confronti della specie umana. Di conseguenza era inclinato alla malinconia e veniva chiamato il “filosofo piangente.”

Interestingly another isolated figure, to the left of Diogenes, is shown in the classical “thinker” position. This brooding man is thought to be the philosopher Heraclitus who eschewed his privileged existence to live in solitude contemplating the meaning of life. He was considered a misanthrope because of his general hatred, dislike, and distrust of the human species. As a result, he was prone to melancholy and referred to as the “Weeping Philosopher.”

Si è a lungo pensato che la figura del meditabondo Eraclito sia un ritratto di Michelangelo, famoso per la sua scontrosità.

It is long thought that the figure of the brooding

Heraclitus is a portrait of Michelangelo,

who was renowned for his grumpiness.

Oh, essere stata una mosca sul muro quando Michelangelo ha dato un’occhiata al dipinto di Raffaello per la prima volta! L’ha trovato un insulto? Si è arrabbiato? Ma forse avrebbe potuto sentirsi ancora più infuriato quando Raffaello, il favorito personale del Papa per i suoi modi affascinanti e il modo in cui vestiva, quando un ambasciatore annunciò erroneamente che la Cappella Sistina era stata decorata da Raffaello.

Oh, to have been a fly on the wall when Michelangelo got a gander of Raphael’s painting for the first time! Did he see it as an insult? Was he angered? But, he might have felt even more incensed when Raphael—the personal favorite of the Pope for his engaging ways and his elegant clothes—when an ambassador mistakenly announced the Sistine Chapel had been decorated by Raphael.

Alla fine però Michelangelo ha avuto l’ultima parola. Visse fino a ottantotto anni e continuò a lavorare in Vaticano, progettò persino la massiccia cupola su San Pietro.

But in the end, Michelangelo had the last say. He lived to be eighty-eight and continued to work in the Vatican—even planned the massive dome over St. Peters.

D’altra parte, Raffaello ha avuto una vita breve. Morì all’età di trentasette anni, secondo quanto riferito, per una malattia sessuale che aveva contratto dalla sua amante. Il suo funerale è stato piuttosto stravagante a cui hanno partecipato grandi folle. Fu sepolto nel Pantheon e sulla sua tomba è inciso in latino: “Qui resta quel famoso Raffaello dal quale la Natura temeva di essere conquistata mentre viveva, e quando moriva temeva di morire.”

On the other hand, Raphael lived a short life. He died at the age of thirty-seven reportedly from a sexual disease he contracted from his mistress. His funeral was quite extravagant attended by huge crowds. He was buried in the Pantheon and on his tomb is engraved in Latin: “Here lies that famous Raphael by whom Nature feared to be conquered while he lived, and when he was dying, feared herself to die.”

Al momento della morte di Raffaello non c’erano omaggi di Michelangelo. Qualche anno dopo, quando Michelangelo aveva quarant’anni, scriverà una lettera accusando Raffaello di plagio. Si lamentò inoltre… tutto ciò che Raffaello sapeva sull’arte, lo ricevette da Michelangelo.

At the time of Raphael’s death, there were no tributes from Michelangelo. Rather a few years later, in his forties at the time, Michelangelo would write a letter accusing Raphael of plagiarism. He further complained… everything Raphael knew about art, he got from Michelangelo.

Sono sempre stata affascinata dalla pittura di Rafaello della Scuola di Atene. Lo includo persino in una scena del mio nuovo romanzo “La vita segreta di Sofonisba Anguissola, la donna più famosa di cui non hai mai sentito parlare.” Per saperne di più su Michelangelo e la sua proteggé Sofonisba e la sua reazione alla Scuola di Atene di Raffaello, vi invito a leggere il mio ultimo romanzo, disponibile su Amazon.

I have always been fascinated by Rafaello’s painting the School of Athens. I even include it in a scene in my new novel “The Secret Life of Sofonisba Anguissola—the most famous woman you’ve never heard of.” To learn more about Michelangelo and his proteggé Sofonisba and her reaction to Raphael’s School of Athens I invite you to read my latest novel, available on Amazon.