La Chimera di Arezzo è considerata il miglior esempio di antica opera etrusca. Fu trovato ad Arezzo, un’antica città etrusca. Secondo la mitologia greca la Chimera o “capra” era una mostruosa creatura ibrida che sputa fuoco e che lega più parti di animali per creare una singolare creatura innaturale. La Chimera devastò le terre e Lobates, re della Licia ordinò a un giovane guerriero di nome Bellerofonte di uccidere la temuta bestia. Bellorofonte partì per il suo cavallo alato, Pegaso, e uccise la Chimera, vincendo la battaglia e la mano della figlia di Lobates e del regno. Questa particolare statua della Chimera fu scoperta il 15 novembre 1553 nei pressi della porta di San Lorentino ad Arezzo durante la costruzione della fortezza di Cosimo I de’ Medici che ora si trova vicino al Prato in cima alla collina di Arezzo. La statua fu rapidamente rivendicata dai fiorentini e esposta pubblicamente a Palazzo Vecchio a Firenze.

The Chimera of Arezzo is regarded as the best example of ancient Etruscan artwork. It was found in Arezzo, an ancient Etruscan city. According to Greek mythology, the Chimera or “she-goat” was a monstrous, fire-breathing hybrid creature binding multiple animal parts to create a singular unnatural creature. The Chimera ravaged the lands and Lobates—the King of Lycia—ordered a young warrior named Bellerophon to slay the dreaded beast. Bellerophon set out on his winged horse, Pegasus and slew the Chimera, winning the battle and the hand of Lobates’ daughter and the kingdom. This particular statue of the Chimera was discovered on November 15, 1553, near the San Lorentino gate in Arezzo during the construction of Cosimo I de Medici’s fortress which now graces the Prato at the top of Arezzo’s hill. The statue was quickly claimed by the Florentines and publically displayed in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence.

La Chimera ora risiede nel Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Firenze, ma gli Aretini vorrebbero che la statua fosse restituita dove era stata originariamente scoperta. Se desiderate partecipare a questo sforzo, vi preghiamo di firmare la petizione per restituire la Chimera ad Arezzo!

The Chimera now resides in the National Archaeological Museum in Florence, but the Aretini would like the statue returned to where it was originally discovered. If you’d like to be part of this effort, please sign the petition to return the Chimera to Arezzo!

Sign the Petition!

Now, in a guest article by Debora Bresciani,

here is a more detailed accounting of

the legend and history of Arezzo’s Chimera.

Ciao! Torno a parlarvi di qualcosa di molto importante per la mia città di Arezzo, la statua di bronzo etrusco della Chimera, purtroppo conservata ancora oggi a Firenze ma ritrovata e appartenente ad Arezzo. Da noi ne possiamo vedere solo alcune copie davanti alla stazione ferroviaria, a porta San Lorentino dove è stata trovata e una copia in scala all’interno del palazzo della Provincia. Se vi va scopriamo insieme di cosa si tratta.

I’m back to tell you about a very important part of my city of Arezzo—the Etruscan bronze statue of the Chimera, which unfortunately while discovered in Arezzo is l preserved today in Florence. Currently there are just copies of this statue that you can see in front of the train station, and in front of Porta San Lorentino where it was originally found and inside the Palazzo della Provincia. If you like, let’s discover more about this statue—the Chimera!

Il mito di Chimera

La Chimera è la personificazione della Tempesta, la sua

voce è il tuono.

Figlia di Echidna (per metà donna e per metà serpente) e Tifone (mostro capace

di incutere timore persino a Zeus), genitori anche della Sfinge, di Cerbero e

dell’Idra di Lerna. Secondo la mitologia Chimera dimorava in Licia, dove

distruggeva ogni cosa con le fiamme che uscivano dalle sue tre bocche.

The Chimera is the personification of the Thunderstorm, its voice is the thunder. It is the daughter of Echidna (half woman and half snake) and Typhon (a monster that inspired fear even in Zeus). These two were also the parents of Sphinx of Cerberus and of Idra of Lerna. According to mythology, the Chimera lived in Lycia, where it destroyed everything with the flames the shot forth out of its three mouths.

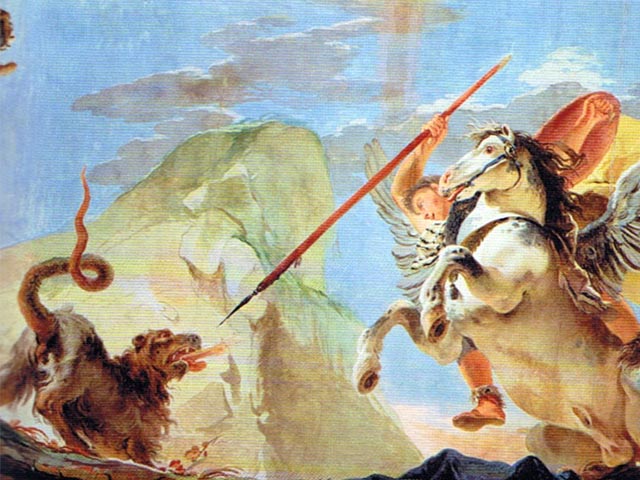

Fu Bellerofonte, eroe da molti ritenuto figlio del dio Poseidone, a fermare le scorribande del mitico mostro. Con l’aiuto di Pegaso, cavallo alato, Bellerofonte riuscì a sconfiggere Chimera con le sue stesse, terribili, armi, infatti “…non c’era freccia o lancia che avrebbe presto potuto ucciderla.” Allora Bellerofonte immerse la punta del giavellotto nelle fauci della belva, il fuoco che ne usciva sciolse il piombo che uccise l’animale. Come già aveva fatto Perseo con Medusa, anche Bellerofonte abilmente seppe sconfiggere la creatura facendo si’ che la sua forza si ritorcesse contro di lei.

It was Bellerophon the son of the god Poseidon, whom many already considered a hero, who finally stopped the raids of this mythical monster. With the help of Pegasus, a winged horse, Bellerophon was able to defeat the Chimera with his own terrible weapons, because there was no regular arrow or spear that could kill her. So Bellerophon dipped the tip of his javelin into a poisonous lead and when he pierced the beast directly in its mouth the metal melted into its throat and killed the animal. Just as Perseus killed the Medusa, Bellerophon defeated the creature by causing its strength of the beast to turn against itself.

Molte e diverse sono le rappresentazioni iconografiche del mostro leggendario. Dall’Iliade sembra ispirato l’artefice della Chimera di Arezzo, leone davanti, capra sul dorso e serpente dietro.

There are many iconographic representations of the legendary Chimera monster. From the Iliad it seems the version found in Arezzo inspired the story: lion in front, goat on the back and snake from behind.

“Lion la testa, il petto capra, e drago la coda;

e dalla bocca orrende vampe vomitava di foco …

(Iliade, VI, 223-225 trad.V.Monti)

Chimera aveva il corpo di un leone, con tanto di criniera (sebbene fosse ritenuta una femmina), ma al posto della coda le spuntava un serpente, e dalla schiena scaturiva una terza testa, quella di una capra. In apparenza tutte e tre le teste erano in grado di soffiare fuoco.

Chimera had a body of a lion, complete with a mane (although it was considered a female), but instead of a tail, a snake was sticking out of it, and from the back sprang a third head, that of a goat. All three heads were able to blow fire.

La Chimera d’Arezzo

La Chimera di Arezzo è un bronzo etrusco, probabilmente opera di un’équipe di artigiani attiva nella zona di Arezzo. È il simbolo del Quartiere di Porta del Foro, uno dei quattro quartieri della Giostra del Saracino di Arezzo. La sua datazione è fatta risalire a un periodo compreso tra il V e il IV secolo a.C. Faceva parte di un gruppo di bronzi sepolti nell’antichità per poterli preservare.

The Chimera of Arezzo is an Etruscan bronze, probably the work of a team of artisans active in the Arezzo area. It is the symbol of the Porta del Foro district, one of the four districts of the Giostra del Saracino of Arezzo. It dates back to the 4th and 5th century BC. It was part of a group of bronzes buried in antiquity to preserve them.

Si tratta di una statua di bronzo rinvenuta nel novembre del 1553 in Toscana, ad Arezzo durante la costruzione di fortificazioni medicee, fuori da Porta San Lorentino (dove oggi si trova una replica in bronzo). Venne subito reclamata dal granduca di Toscana Cosimo I de’ Medici per la sua collezione, il quale la espose pubblicamente presso il Palazzo Vecchio, nella sala di Leone X. Venne poi trasferita presso il suo studiolo di Palazzo Pitti, in cui, come riportato da Benvenuto Cellini nella sua autobiografia, “il duca ricavava grande piacere nel pulirla personalmente con attrezzi da orafo.”

This particular bronze statue was found in November 1553 in Tuscany in Arezzo during the construction of the Medici fortress, outside Porta San Lorentino (where today there is the bronze replica). It was immediately claimed by the Grand Duke of Tuscany Cosimo I de’ Medici for his collection, which he displayed in the Palazzo Vecchio, in the room of Leo x. It was then transferred to his study in the Palazzo Pitti, where, as reported by Benvenuto Cellini in his autobiography, the duke took great pleasure in personally cleaning it with goldsmith tools.”

Nel 1718 venne poi trasportata nella Galleria degli Uffizi e in seguito fu trasferita nuovamente presso il Palazzo della Crocetta, dove si trova tuttora, nell’odierno Museo archeologico di Firenze.

In 1718 the Chimera was transported to the Uffizi Gallery and then later to the Palazzo della Crocetta, where it is still today, in the present Archaeological Museum of Florence.

Inseguire una Chimera

Italian Expression of the Day!

La Chimera, con le sue strane fattezze, personifica qualcosa di molto lontano dalla realtà, un insieme di elementi che in natura non avrebbero mai potuto essere legati tra loro, per questo nel linguaggio di tutti i giorni l’espressione “Inseguire una chimera” significa perdersi dietro qualcosa di illusorio, un sogno vano e difficilmente realizzabile che ci svia dalla concretezza della vita reale.

The Chimera, with its strange features, personifies something very far from reality, a set of elements that in nature could never exist. So, in the Italian language, there is the expression “Chasing a chimera” which means to get lost in a vain dream or try to achieve something that isn’t feasible.

Sign the Petition!

Per favore firmate la petizione per restituire la Chimera ad Arezzo. Credo che in questo caso non inseguiamo una Chimera! Potrebbe succedere con il vostro aiuto!

Please sign the petition to return the Chimera to Arezzo. I believe, in this case we are not chasing a Chimera! It could happen with your help!

Join me in Arezzo in June to learn more about the Chimera in person!

If you are traveling on your own, be sure to contact Debora for a guided walking tour of the city and learn more about Arezzo’s churches, history, and legends!

If you liked this post you might like these posts too!

Italia – I love your contrasts!